American Dreamer

Logan, Utah wasn't the stuff of his Hollywood-based imaginings, but it became home to one foreign dreamer who worked hard, overcame many obstacles, and never gave up on the starry-eyed notion of making the world a better place.

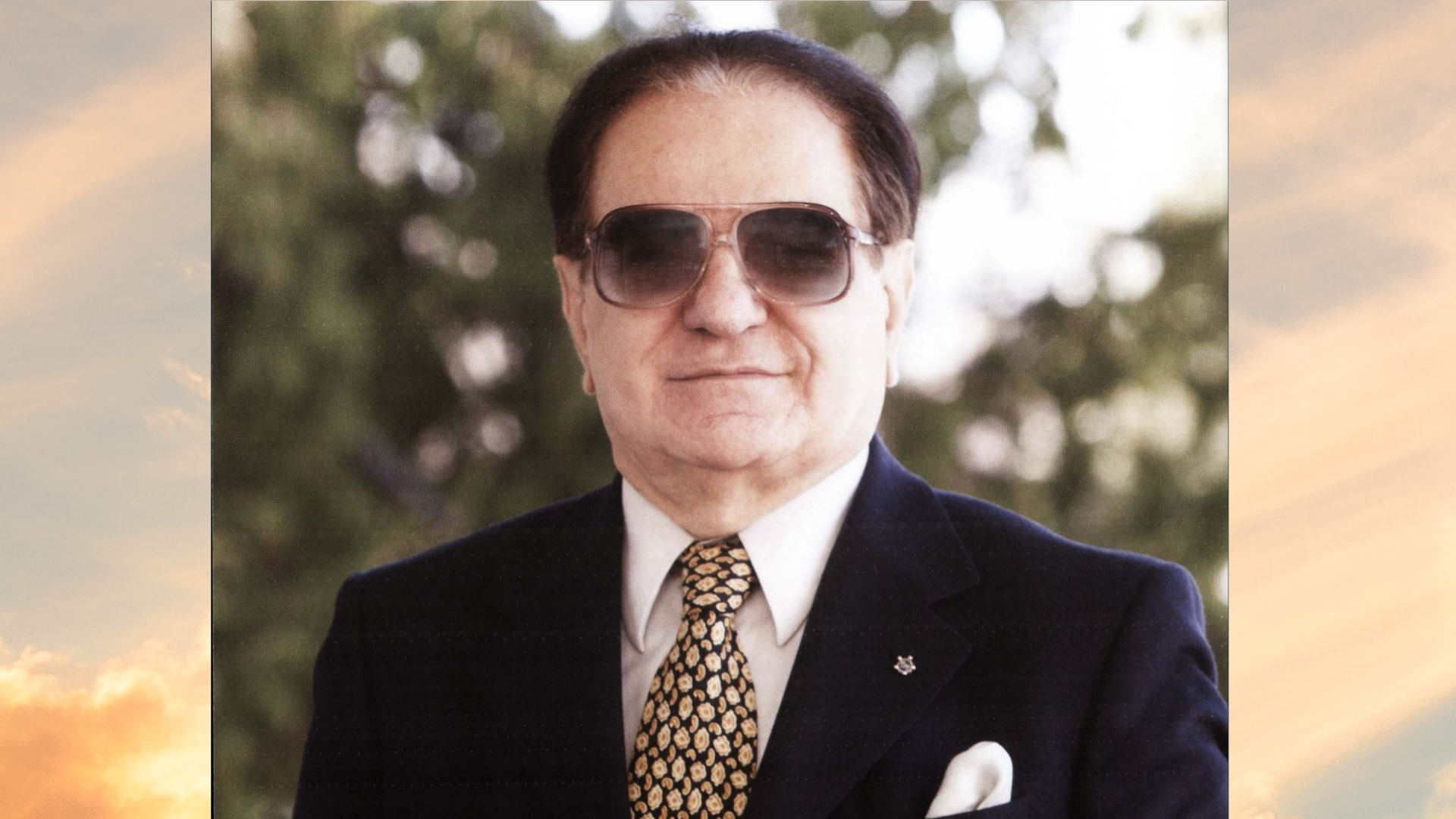

Dr. Mehdi Heravi, scholar, author, philanthropist, and USU College of Humanities and Social Sciences graduate fell in love with the United States through the flickering Hollywood images he couldn’t get enough of as a boy.

“I used to watch American movies all the time during the holidays – Christmas and so on – because we weren’t allowed to watch them when we were in school,” Heravi explained.

The movies mostly depicted America’s big cities, New York and Los Angeles, as well as the flashy cars he knew came from a city called Detroit. To the young Heravi, the angled cityscapes in CinemaScope and moody, soft-edged, Technicolor romances were the United States, and he longed to be there.

Heravi’s father, however, would not hear of such a thing. Born in Tehran, Iran, Mehdi Heravi was part of a large, well-to-do, and well-educated family. His father had received his schooling at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris and in the early 1950s, when Heravi and his older brother were deemed at an age to begin their more formal educations (Mehdi was nine, his brother, 13), the boys were sent to an esteemed private school in England. It was during that time the future academic began his love affair with America… via film.

“I kept insisting that my father send me to America, but he totally rejected the idea,” Heravi said, explaining that his father feared a lifestyle that would include, “smoking and drinking and becoming a cowboy.”

But even at that young age, Heravi was not one to back away from a challenge, or a dream. Every summer for years, the boy petitioned his father and every year, he would be rejected. That is until Heravi, who was a “favorite of my grandfather,” decided to seek help from the older man to make his dream of a life in America come true.

"I promised my grandfather that if I could go to America I would study hard. I wouldn't smoke, I wouldn’t drink, and I wouldn’t become a cowboy," Heravi said.

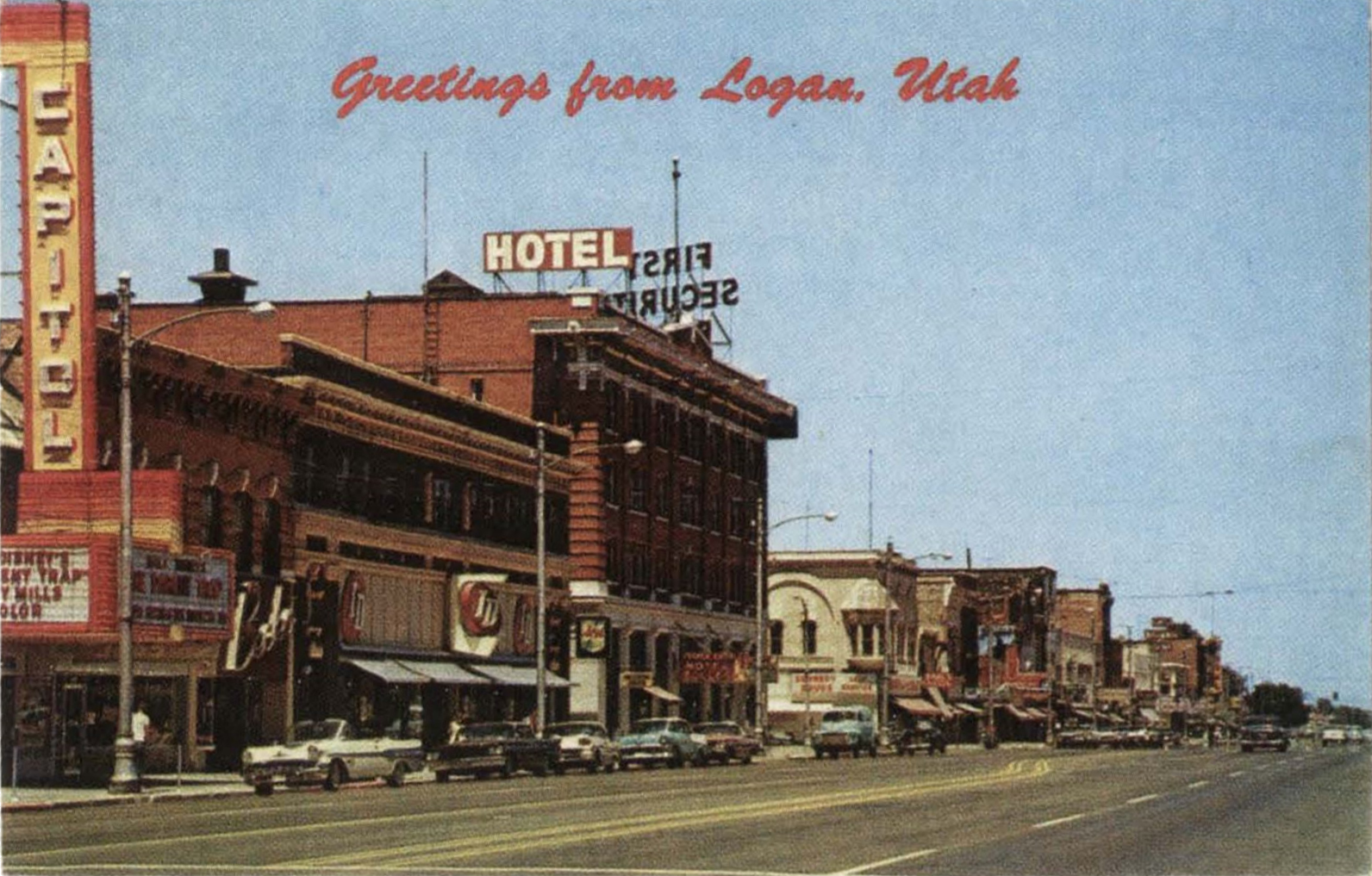

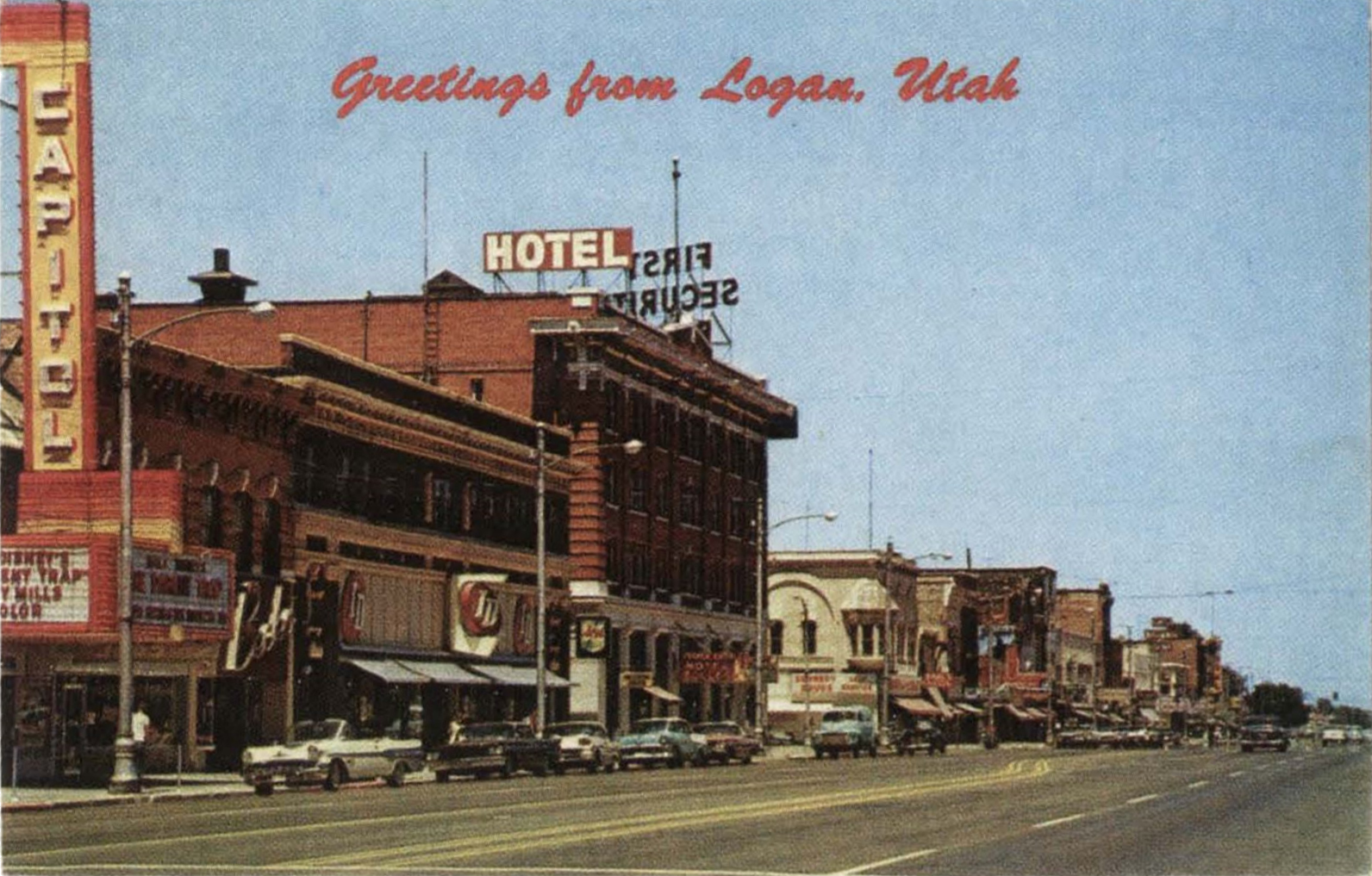

Dr. Mehdi Heravi, born in Iran and educated in England, learned to love the Logan of the 1960s (above). Now making his home in Washington D.C., he returns to the area frequently to reconnect with friends old and new in Logan and on the Utah State University campus.

FROM DREAM TO REALITY

Reluctantly acquiescing to the grandfather’s request, Heravi's father agreed the boy would be sent to the United States for his final year of high school. Although Heravi pictured the bright lights and skyscrapers of Broadway, his father, a professor of agriculture at the University of Tehran, quietly made other inquiries.

''At that time there were several professors visiting the University of Tehran and my father went to these American professors and asked, 'Where in America can I send my son?"' Heravi explained. "They said, 'Professor Heravi, we have a great place for you. It's where we come from. It's called Utah.' And so one day my father said, 'Now I think your grandfather is right and you are going to America. You are going to Utah."

Not long after, arrangements were made for the teenager to make the 24-hour prop plane flight from Tehran to London and finally to New York. After a few days in the city that didn't sleep-but did meet every dreamy expectation the young traveler ever had-the boy boarded another plane to Salt Lake City, a destination he fully expected to be, if not a mirror image, at least a near replica of the Big Apple with which he'd already fallen in love.

The Salt Lake City airport in 1958 was less bustling international travel hub and more small town way station. If the eight-hour trip from New York wasn't disconcerting enough ("I couldn't imagine why it would take so long. Where was I going?"), the high desert in June didn't seem exactly welcoming.

"Looking down from up in the air, there were no trees, nothing," Heravi remembered. “Believe me, coming from London, then New York to Salt Lake City, it was a shock. A real shock."

A short cab ride to the Greyhound station, followed by a meandering bus ride through Salt Lake, then Ogden and Brigham City, and finally, the two-lane road that wound through Sardine Canyon, at last brought Heravi to Logan. He ate his first meal at Dick's Cafe, which doubled as the local Greyhound bus depot, and secured a $3.50-a-night room at the Eccles Hotel, "the best hotel in town."

"I was surprised that the waitress [at Dick's Cafe] knew I was from out of town, but she said she could tell because most teenagers didn’t wear blue suits like I had on," Heravi recalled with a laugh. "When I told her I was from Iran, she said, 'Oh I know where that is. It's next to Bountiful!"

FROM HOMESICK TO HOME

Unfortunately for Heravi that first night in Logan, Iran wasn't next to Bountiful. A ferocious case of homesickness dogged the teen, bur Heravi knew that after his years of pleading, he couldn’t leave America after only a few days. So the next morning, Heravi sought help from the international student advisor at Utah State. That man, George Meyer, rook the high schooler under his wing, helping him to enroll at Logan High and navigating him to find a home in which he could board for the school year.

Even now, more than 50 years later, Heravi speaks fondly of the adults who helped him along the way, Meyer and Sherman Eyre, superintendent of schools at the rime, Fred Sears, and many others. Warmly regarded too are the many friends he made during high school and throughout his USU career. In fact, Heravi remains in close contact with many Utah friends and their families.

"These are some of the best people, the best human beings I have ever met," Heravi said.

Despite admitting that during the first few weeks of his stay in Cache Valley, the young international traveler would have returned home if he were able, Heravi was determined to make a go of it, at least for a while.

"I thought maybe I could make it one year and finish high school and then beg my parents to take me back," Heravi said. "But after that one year, I became involved in Logan, and Logan became a part of me."

After high school, Heravi continued to extend his roots in the community when he enrolled at Utah State. At the university he studied political science, eventually earning both bachelor's (1963) and master's (1964) degrees.

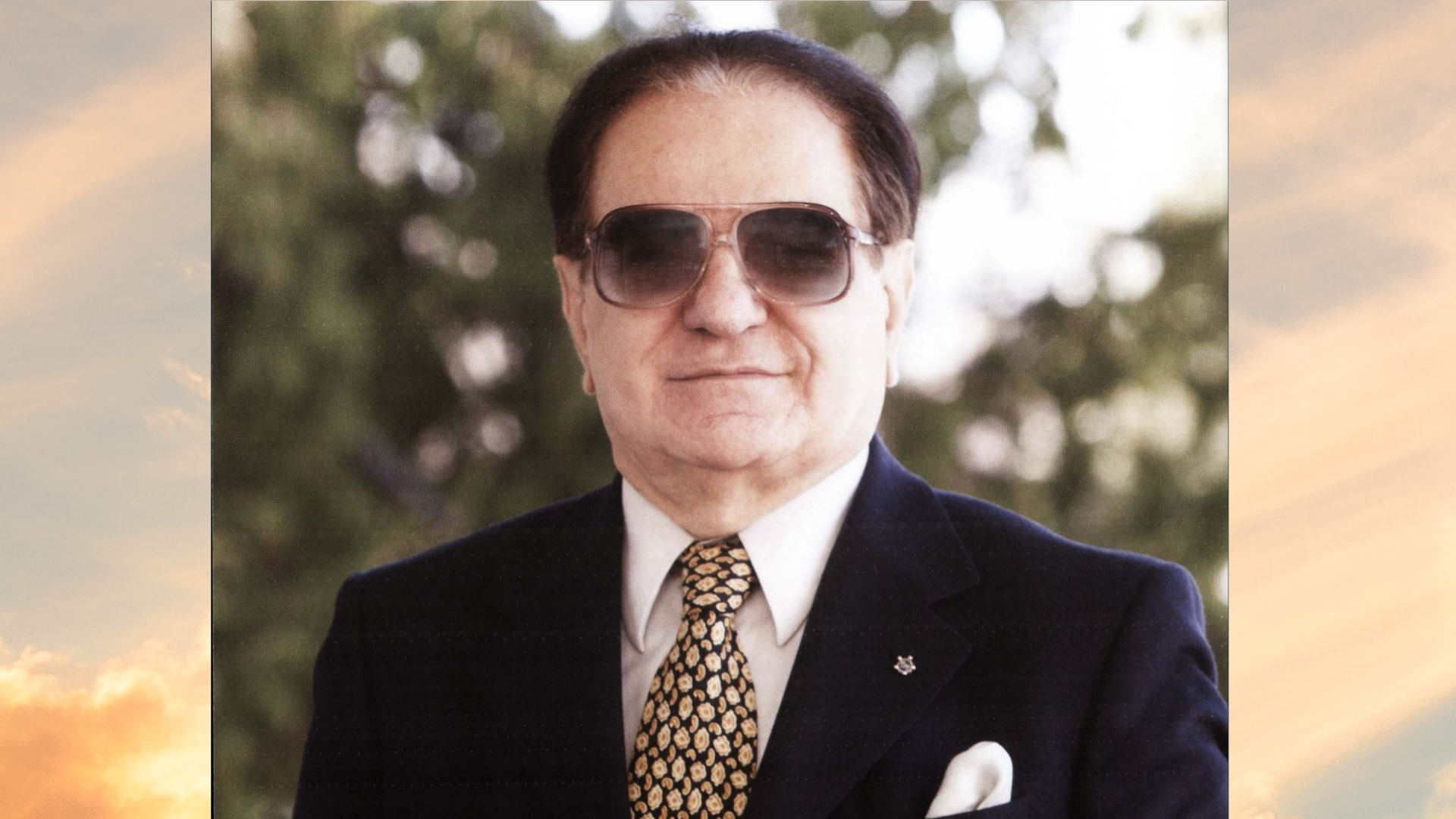

Dr. Mehdi Heravi received both his bachelor's and master's degrees from USU's College of Humanities and Social Sciences. He also was a member of the USU Student Senate.

His education at Utah State, Heravi feels, was exceptional. But – and as many a USU alum can attest – behind the academic rigors, Heravi said, were the people who inspired him, nurtured him, and whom he came to respect and love.

"Milton Merrill [who was serving as professor of political science, and the university’s first vice-president]. He was something unusual: a brilliant man, a great human being. I admired him so much. He was like a second father to me," Heravi said.

Also on his list of admirable mentors is then university President Daryl Chase.

“President Chase was a trued visionary and a wonderful human being,” Heravi said. “He also became like another father to me.”

Heravi was something of a visionary himself, at least when it came to believing in his own plans and never letting fear get in the way of what seemed like a good idea. Such was the way in which the young Iranian became the first international student in the history of Utah State to run for Student Senate, not for the position of “International Senator” as his friends expected and as would have been the norm for an international student, but for the campus-wide position of “Independent Senator.”

"Everyone, literally everyone said, 'You're going to get clobbered."' Heravi remembered with a la ugh. "There were 17 people in the primary and I defeated 11 of them; and then in the final, I defeated the rest of them."

FROM SCHOLAR TO PHILANTHROPIST

It was those kinds of extraordinary experiences along with his USU CHaSS education and the people he encountered along the way that made Heravi very reluctant to leave Logan, though he knew he must if he was to achieve his goal of earning a PhD. Still, he couldn't quite let go.

"I really didn't want to leave Logan so I delayed leaving for one year. They gave me a teaching assistantship in political science that I loved, but I finally left in 1965 to go to American University School of International Service in Washington, DC," Heravi recalled.

There, at what is now the nation's largest school of international affairs in the United States, Heravi received his PhD in 1967 at the age of 26. Following graduation, and at the height of the Vietnam War when jobs for academics were few and far between, Heravi managed to secure five offers for teaching positions. Although his friends warned him he probably wouldn't like Tennessee, Heravi once again sought his own way and after an initial, extremely welcoming visit, he accepted a teaching position at Tennessee Technological University. During his six years in Tennessee, Heravi said he once again came to love the area and the people who inhabited it. "I made many wonderful, wonderful friends while I was in Tennessee," Heravi said.

The truth is, Heravi makes wonderful friends wherever he goes. In fact, he sees the act of connecting to others as one of the most important parts of being human-reaching out to people, extending the hand of friendship and support-in short, caring.

Honored in 2014 for his philanthropy and devotion to his alma mater, Dr. Heravi is inducted into the Old Main Society. USU President Stan L. Albrecht and his wife, Joyce Albrecht, present Heravi his award during the annual induction ceremony held in November.

In 1973, Heravi received an offer from the National University of Iran to serve as the college's vice president. The opportunity to return to his homeland in a position that seemed a perfect fit was simply impossible to pass up, so Heravi returned to Iran and the university there.

Only six years later, however, the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty and ouster of the Iranian king, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, brought sweeping change to Iran and to Heravi's life. With the rise of an Islamic republic under the rule of Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1979, the higher education system in Iran changed dramatically. The transformation also altered Heravi's life immeasurably, setting him on a completely new life course.

I think it's a moral duty for anyone who has been blessed — and I have been blessed since I was born — to give back, especially to people who are in need.

"I was purged of my position at the university, a retirement through force," Heravi said. "But this is when I decided that it was time to devote myself to philanthropy."

To say Heravi has, since the days of the revolution, devoted himself to philanthropy is to understate vastly the extent of his humanitarian contributions. Among other causes, Heravi helps support an orphanage located in northern Iran along the Caspian Sea. He visits the sire often, delighting in the love he receives from the children there.

“It gives a great deal of satisfaction when you do things for your own children,” Heravi explained, “But with these children, when you do even the smallest thing, you see laughter in their eyes. You see appreciation all over. They come and hug you. It’s a very good feeling. That orphanage is a big part of my life, definitely.”

Heravi also helps support several organizations related to cerebral palsy, a disease that afflicts his son.

"I kept thinking that if I call myself a human being, then these people who help take care of my son and who take care of special needs individuals full-time with love and devotion, these people are angels," Heravi said.

When it comes to remembering his alma mater, Heravi is no less generous. Having already established an agricultural scholarship in his father's name and another for education students intending to help those with special needs, Heravi in October visited CHaSS Dean John C. Allen's office to offer the details of a new scholarship he has since established in the department from which he graduated. He also stopped by Logan High School to offer that institution a scholarship in his name.

Even as he travels from his home in Washington DC to destinations across the country and around the globe, Heravi said Utah State, his friends in Logan, and others around the world are always on his mind. And what he thinks about most is how he can give back to all of them.

"You know, you reach a certain age and you feel that you have been blessed in your life and you realize millions and millions of people in this world are not as blessed," Heravi said. "So, I think it's a moral duty for anyone who has been blessed -and I have been blessed since I was born -to give back, especially to people who are in need."

Those who may marvel at Heravi's generosity on so many fronts likely will have much more to be astonished by, because, according to Heravi, "These are first steps as far as I'm concerned. Hopefully, I will be doing much more in the future." For young people looking to him as an example, Heravi has a bit of well-rehearsed advice. Though he may have spoken the words many, many times over the years, they express a truth he holds dear to his heart, a truth that continues to guide his life more than 50 years since a wide-eyed Iranian school boy arrived alone in Logan, Utah.

"I have faith in humanity. And hopefully I will continue to have good health so I can achieve the things I want to achieve," Heravi said. "You know, a low aim in life is a crime. The sky is the limit and humanity is the priority."