The EU’s Carbon Border Tax Disrupts Global Economic Flows

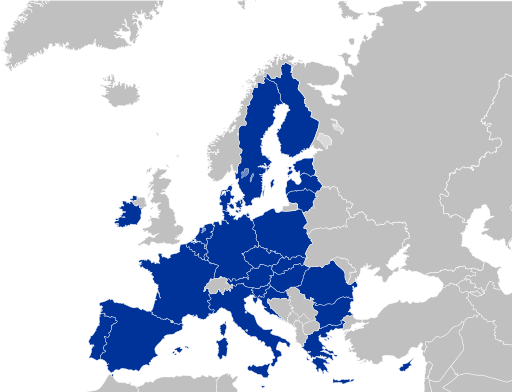

European Union member states.

Anna Johnson - With its global scale, climate change is one of the central challenges governments worldwide must face. States have tried various methods to stem their carbon pollution to varying degrees of success, but economic interests have slowed progress in this area. Most states struggle to find a balance between environmental protection and the stability of their economies, often choosing economics over climate action. The European Union, however, has a strategy for climate action that uses economics as a tool for environmental protection rather than as an opposing force.

The EU placed a carbon dioxide emissions tariff on imports of goods such as iron, steel, fertilizer, and other sources of pollution. The tariff would require importing companies to buy certificates to cover the carbon dioxide emissions of their imported goods. Companies within the EU are already required to buy permits for their carbon dioxide pollution, but this new rule would apply the same standard to overseas firms. The tariff affects two major flows: the flow of pollution from factories in the EU into the atmosphere, and the economic flow of goods in and out of the EU. In an era of globalized trade, the carbon tax is intended to protect domestic manufacturing from being undercut by foreign manufacturers not subject to the EU’s Fit for 55 program which aims to cut CO2 emissions from the EU by 55% by 2030. Inspired by the EU’s tax, the United Kingdom, Canada, and even some officials in the United States have considered creating a carbon tax of their own - both as a form of climate action and a response to the EU’s policy. The added cost of importing goods from high-emitting countries has the potential to detach the European Union from global trade flows, further distinguishing the region from neighboring non-member countries.

As a functional region, the European Union is already distinct from the rest of Eurasia to an extent. While sharing similar cultural and geographic makeups, non-EU member states like Turkey and Switzerland are not part of the region and would be subject to these carbon taxes. Turkey, in particular, has taken issue with this economic isolation and the accompanying tariffs. Non-European developing states have similar concerns, paired with the added burden of economic growth under increasing pressure to develop without the same fossil fuel crutch developed economies relied on.

Picture Credit: Photo distributed under the GNU Free Documentation License. Source